Climate change is real! That’s the rallying cry for carbon dioxide scolds in the wake of any abnormal storm in the 21st century. Here’s what else is real: Energy transition is complicated.

And nowhere are the complications more apparent than in transportation, manufacturing and other hard-to-transition (HTT) sectors.

The most recent Energy Transition Outlook [https://bit.ly/3YWr1Jn] from global risk management company DNV makes it clear that there is no shortcut off-ramp to electrification for HTT sectors – no matter how loud the noise from fossil fuel opponents.

That is not to say that no progress has been made. But if global HTT sectors are to reach anywhere close to net zero, they will need billions of investment dollars for innovation and infrastructure. They and the rest of the world will also need regional and international political co-operation, standardized regulation and bold corporate, consumer and political leadership.

All of that is in short supply today. And because the West’s education system appears now to excel in churning out advocates for political causes rather than seekers of bipartisan solutions to complex problems, that supply won’t increase any time soon.

Still, there is some good energy transition news to report.

As DNV’s CEO Remi Eriksen notes in his introduction to the company’s Energy Transition Outlook, 2024 marks the year the global energy transition has begun in earnest. It will also be, he adds, the year that global emissions are likely to peak.

But Eriksen points out that DNV’s forecast decline in global carbon emissions “worryingly … is very far from the trajectory required to meet [Paris Agreement targets].”

The result, according to the DNV report’s “most likely” energy transition scenario, “leads to warming of 2.2°C by the close of this century.”

With a world population forecast to increase 20% by 2050 and a global GDP expected to double during that time, industries, consumers and countries will need more energy and more energy services.

How much?

DNV estimates 80% more.

But, the company’s report concludes that overall energy demand will grow by only 10% between now and 2050.

Why?

Electrification’s energy efficiency.

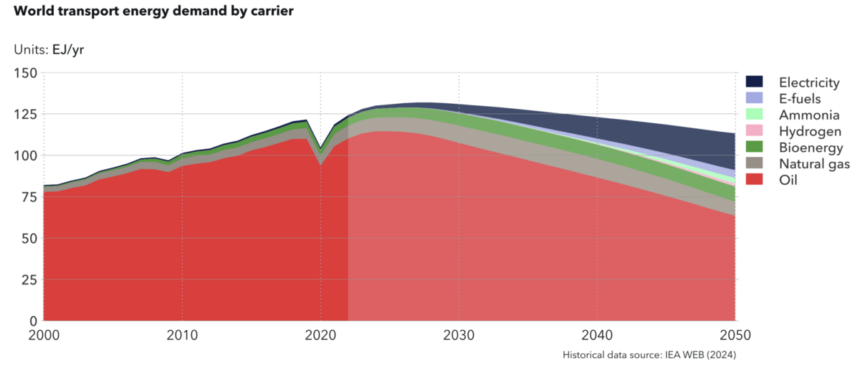

However, technological and marketplace viability hurdles for electrifying shipping and aviation limit electrification’s application in those sectors.

Add in the investment required to decarbonize container shipping – approximately US$1.6 trillion to hit the International Maritime Organization’s [IMO] ambition of zero-emission shipping by 2050 – and you can see why Danish Ship Finance’s [DSF] November report points out that “the shipping industry is struggling to keep up with greenhouse gas [GHG] emission reduction plans.”

The global ship finance company adds that while ocean carriers are harvesting much of the low-hanging GHG reduction fruit, the maritime shipping sector is struggling to tap the resources needed to cut emissions.

That will require sector-wide changes in contracts and behaviour to shift financial and operational priorities.

But, as DSF notes, “The dominant business models currently prioritize short-term gains rather than investments in long-term potential.”

It concludes that the global shipping sector’s lack of emissions transparency and benchmarking is hindering the widespread adoption of emission reduction tools.

Without that transparency and reliable measurement, investors, customers and the overall marketplace cannot make informed decisions that support decarbonization and sustainability goals.

Meanwhile, UNCTAD points out that by early 2024, only 14% of new shipping tonnage was alternative fuel-ready.

However, some progress is being made.

During a recent update on the container shipping industry, Simon Heaney, senior manager of container research at U.K.-based shipping consultancy Drewry, pointed out that approximately 95% of orders for new ships this year have been for those with alternative fuel technologies.

DNV’s report sees a significantly decarbonized maritime shipping sector by 2050 dominated by hydrogen-based fuels [24% ammonia, 12% e-fuel (likely methanol), 11% biofuel].

Electrification’s role on the water will be insignificant (4%). On the road, however, it will be huge. DNV estimates that EVs will account for half of all new vehicle sales by 2031. That will help road-based mobility achieve transportation’s biggest decarbonization gains.

But the market will need amped-up hard-sell tactics today to get anywhere close to hitting that sales target.

McKinsey Global Institute’s The Hard Stuff report [https://bit.ly/3ZhmH80] notes that electrical vehicle deployment is currently only 3% of what would be required to decarbonize road mobility by 2050.

That is just one energy transition challenge for transportation.

Aviation’s energy demand, meanwhile, is predicted to increase by 60% by 2050, and DNV says oil will still service 60% of that demand. Today, it supplies 100%.

Bio-based fuels will be the main alternative here. Unless innovation comes to the rescue.

In the wider world of energy transition, renewable options are gaining ground.

According to the International Energy Agency, global renewable capacity is expected to almost triple (up 2.7 times) by 2030. That would exceed’ current ambitions by nearly 25%.

So, there is progress to report.

But here is the transportation energy transition reality check: Accelerating that progress will depend on strategically targeted investment, innovation and regulation, not bull-horn sloganeering.

timothyrenshaw.substack.com

nonstop@shaw.ca

www.linkedin.com/in/timothyrenshaw

@trenshaw24.bsky.social

@timothyrenshaw