Compared to internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEV), electric vehicles (EVs) cost much less to drive. They also cost far less to maintain. EV adoption rates are rising, especially in states such as California, but even then EVs have an exceptionally low share of vehicles on the road.

As stated on Edmunds: “According to an Experian Automotive Market Trends report from the fourth quarter of 2023, there were about 3.3 million electric cars on the road in the U.S. This number is up from 2 million electric vehicles in 2022 and 1.3 million in 2021. While EVs are gaining traction, they are still a long way from catching up to gas-powered vehicles, which make up the remaining 288.5 million cars currently in operation. By 2030, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory predicts there could be 30 million to 42 million EVs on U.S. roads.”

When discussing the low adoption rate of EVs, analysts cite the following four barriers: range anxiety, high capital costs, lack of multiple models, and the newness of the technology.

But newer EVs have a longer range than those that were on the market a decade ago. More charging stations are being installed nationwide. Both factors should address driver anxiety about running out of range on a long drive.

Capital costs are coming down. I bought a 2024 “Highland” Model 3 for $40,600 in November. It has a Dual Motor (All Wheel Drive) and a range of 341 miles.

The number of EV models has grown rapidly over the past years. Tesla is the dominant brand, accounting for more than half of EVs on the road. But, according to Consumer Reports, a variety of other brands are offering EVs including Audi, BMW, Chevrolet, Ford, Kia, Hyundai, Kia, Lucid, Mercedes Benz, Nissan, Polestar, Porsche, Toyota, Volkswagen and Volvo. Altogether, more than four dozen models of EVs are available today.

Finally, EVs are no longer the exotic new technology they once were. So, each of the four barriers is being addressed.

But there is a fifth barrier that is being overlooked by most EV analysts. It is the threat posed by rising electric rates, especially in states such as California, New England and New York, which already have high electric rates.

What will happen to the savings in driving costs when electric rates keep on rising? Those savings will begin to evaporate.

And what will happen to the adoption rate of EVs when the savings in driving cost disappear? While rising electric rates may not affect early adopters, they will have a significant impact on mainstream drivers. The EV adoption curve may begin to flatten faster than it would have if electric rates had not risen.

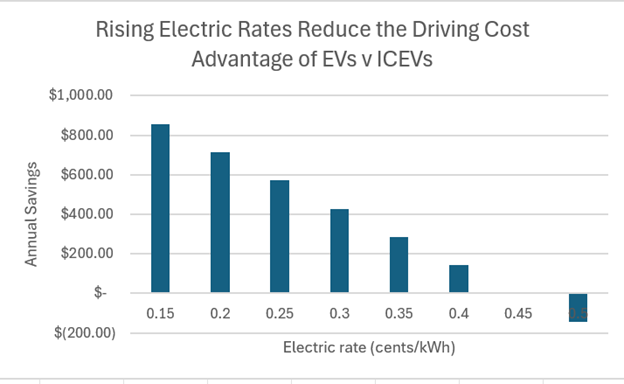

A simple numerical example can be used to illustrate the impact of rising electric rates on the savings in driving costs. I have constructed this using data from Northern California, specifically from the Bay Area in California. It is worth nothing that California, with 12% of the US population, is the national leader in EVs, with 33% of the national EV population.

The San Francisco Bay Area is one of those areas where one cannot avoid spotting an EV, whether at a traffic light, while driving around town, at parking lots in grocery stores, shopping malls, offices, and airports, and on freeways. Most of them are made by Tesla.

How long is that EV dominance of California going to continue? Probably not that long, especially if rates keep on rising at multiples of the rate of inflation. That trend is very visible when observing the behavior of prices in a rate that is widely used by EV drivers, the EV2-A rate of Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E).

What will happen to the savings in driving costs if the rates at which drivers charge their EVs continue to rise? To answer that question, I have made a few assumptions:

•Driving conditions = 10,000 miles per year

•Energy efficiency of an Internal Combustion Engine Vehicle (ICEV) = 35 miles/gallon (Toyota Camry)

•Energy efficiency of an Electric Vehicle (EV) = 3.5 miles/kWh (Tesla Model 3)

•Gasoline price = $4.5/gallon (Regular)

The graph shows the impact of rising electric rates on the savings in driving costs of an EV versus an ICEV when electricity costs rise from 17 cents/kWh to 50 cents/kWh. It’s not pretty!

California has some very aggressive goals regarding EV adoption. How will those be realized unless a cap is put on rate increases? It’s time that the state’s energy policy makers, the California Energy Commission and the California Public Utilities Commission, began paying attention to this issue.