Originally published in MasterResource.

Wind and solar have been growing as a share of US electrical power generation over the last two decades. State and federal mandates and subsidies have driven the expansion of renewables. But it’s clear that renewable electricity sources are fragile and prone to weather damage and destruction.

Twenty-three states now mandate Net Zero electricity by as early as 2035. Their aim is to replace coal- and gas-fired power plants with wind and solar generators. Wind and solar have grown from near zero in 2000 to 14.1% of US electricity generation in 2023 (10.2% wind and 3.9% solar).

Wind and solar systems are located on ridge lines, on plains, and offshore, and are exposed to weather forces that usually don’t affect building-housed coal and gas generators. In addition, these systems require about 100 times the land area of traditional generators to deliver the same average electricity output, increasing the chances of storm damage. Damage incidents are rising as more and more systems are deployed.

In May 2019, a massive hailstorm in West Texas destroyed 400,000 solar modules of the Midway Solar Project, about 60% of the facility. The project was only one year old. The system was rebuilt, costing insurers more than $70 million.

On June 23, 2023, the Scottsbluff solar system was destroyed in western Nebraska. Baseball-sized hail falling at up to 150 miles per hour smashed most of the 14,000-panel system. The system had only been operating for four years of its 25-year lifetime and had to be completely rebuilt.

Solar loss insurance claims from hail damage now average about $58 million per claim. Hail damage claims have increased to account for about 54% of solar insurance loss claims. Analysis by Iowa State University shows that severe hail (greater than one inch in diameter) can occur for 20 to 30 days per year in Great Plains states, a wide area of the country stretching from North Dakota to Texas and Colorado to Indiana.

“Fighting Jays Solar” became operational in July of 2023, 40 miles northwest of Houston, Texas. Less than one year later, on March 15 of this year, hail destroyed much of the system, with repair costs estimated to be hundreds of millions of dollars. The system had not yet completed full construction.

Hail is not the only weather hazard facing solar installations. This fall, a tornado associated with Hurricane Milton destroyed much of the Lake Placid Solar Plant in Sylvian Shores, Florida. The facility had only been operating for about five years.

As a result of hail and other weather damage, insurance premiums for solar facilities are skyrocketing, in some cases up by as much as 400%. In addition, policy coverage is being capped at as little as $10-15 million, requiring system developers to obtain multiple policies to try to cover their projects.

The federal government has been promoting the installation of wind systems off the US East Coast. Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, South Carolina, Rhode Island, and Virginia are constructing or planning offshore wind systems. But offshore wind must operate in one of the world’s harshest environments, buffeted by wind, waves, lightning, and salt spray that is very corrosive to man-made structures.

To date, most offshore wind systems have been deployed in China, Europe, and Vietnam. These systems are prone to weather damage. Turbines deployed in Asia coastal areas suffer typhoon wreckage. Eighty percent of the turbines installed in Europe’s North Sea have required repairs due to weather damage.

The London Array, east of England, the world’s largest offshore wind system, required extensive repairs after only five years of operation. Danish wind operator Ørsted needed to repair undersea cables to offshore wind systems in the North Sea at a cost that exceeded $100 million.

But turbines sited off the US East Coast must survive brutal weather, more severe than offshore turbines in Europe. Tropical storms, hurricanes, and nor’easters periodically traverse the coastal sites planned for new offshore wind systems.

For example, historical data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration shows that 26 hurricanes and 51 tropical storms passed through New Jersey coastal waters during the last 170 years, or almost five storms each decade. Wind installations will be vulnerable to these weather systems.

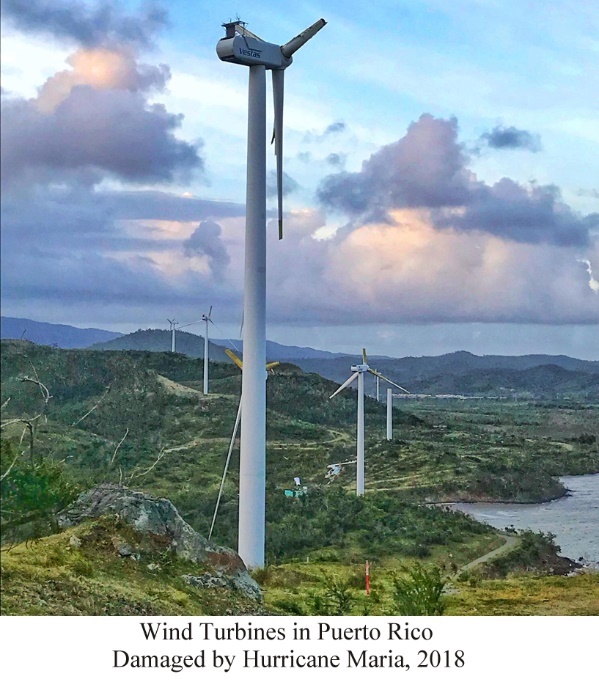

In 2018, Hurricane Maria passed over Puerto Rico, ripping blades from many turbine towers. East Coast wind systems will likely suffer the same fate.

Wind systems are designed to try to protect wind towers and blades in high winds. When winds exceed 55 MPH, a braking system brings the rotor to a standstill to try to avoid turbine damage. Tower blades are also “feathered” or oriented so that they no longer catch the wind.

But near the eye of a hurricane or tropical storm, violent winds can change direction instantaneously and powerfully, too fast for damage-prevention systems to react. The result will be destroyed blades and damaged towers.

In July, a 351-foot-long offshore wind blade splintered and washed up on the beaches in Nantucket, Massachusetts. Beaches were closed and clean-up crews collected six truckloads of fiberglass and plastic debris from the single destroyed blade. Wind operations were temporarily shut down.

Residents, beachgoers, fishermen, and local businesses posted signs, complained to the press, and spoke out at board hearings. But this was just one turbine blade. Image the outcry when a whole offshore system is destroyed by a hurricane, producing mountains of beach debris at Myrtle Beach, Virginia Beach, Atlantic City, or Long Island?

Media headlines claim that weather is becoming more extreme because of human-caused climate change. But to solve the problem, it’s proposed that we install more and more wind and solar systems, which are fragile and vulnerable to violent weather. Incidents of weather destruction of wind and solar installations will continue to rise.

Steve Goreham is a speaker on energy, the environment, and public policy and author of the bestselling book Green Breakdown: The Coming Renewable Energy Failure.