Summary: We live in a conflict-filled world today. I believe that this is ultimately a “not-enough-to-go-around” problem. Hidden oil shortages are the problem. Strangely, at this stage in the economic cycle, oil shortages seem to appear as high interest rates rather than high prices. The “climate is our biggest problem” narrative gets told repeatedly because it makes cutting back on fossil fuels sound like a virtuous thing, rather than something we are being forced to do.

Introduction: When a major change occurs, such as moving to a new home, there are always a variety of explanations as to why the change took place. When explaining the change to someone else, we will almost always give a positive reason for the move, such as moving to be closer to relatives, access to better job opportunities, or to enjoy a better climate. We don’t talk more than necessary about negative issues such as being fired from a job, undergoing bankruptcy, or considering a divorce from one’s spouse.

With oil shortages and other energy problems (including the possibility of too much fossil fuels leading to climate change), the situation is in some ways similar. There is no simple answer as to why these problems are occurring. What we end up with is different groups seeing the current situation and its long-term resolution from different perspectives. Each group emphasizes the aspects of the problem that they see as most amenable to being solved. The different perspectives lead to conflicts among the groups.

We are living in a finite world. It is not clear that any perfect solutions are at hand. What is clear is that a finite world behaves very differently from what our intuition or the models created by economists suggests. In this post, I will try provide a partial explanation of what our energy dilemma entails, and how this leads to conflict, even war.

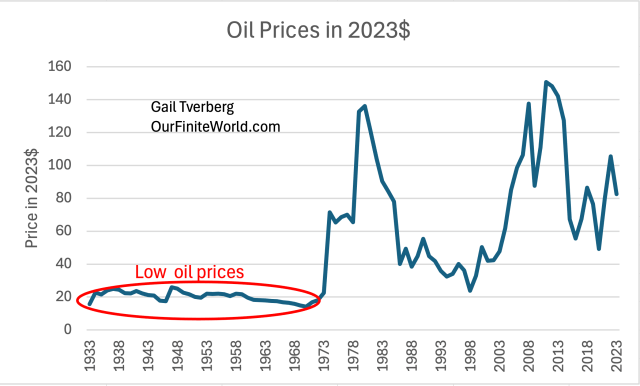

[1] World crude oil supply suddenly “turned a corner” about 1973. There was a huge change both in the price and growth rate of the oil supply.

Prices were amazingly low prior to about 1973. The prices shown have been adjusted for inflation to the 2023 price level.

Once oil prices rose, the growth rate of oil consumption collapsed because goods and services made with oil were no longer as affordable. There was also an effort to cut back on oil consumption because it was clear that low-cost oil supply was limited.

Increases in the supply of very cheap oil allowed many improvements to infrastructure. Electricity transmission lines, interstate highways, long distance oil and gas pipelines, and infrastructure supporting transport by air were all added. The economy became more productive. Figure 3 shows that the wages of even low-paid workers were able to rise.

Up until 1968, US wages for both the bottom 90% of workers and the top 10% of workers rose much faster than inflation. With this change, all kinds of goods and services became more affordable, including food, new homes, and new cars. In the period 1968 to 1981, the wages of both groups rose as fast as inflation. After 1981, growth of the wages of the top 10% far exceeded the inflation rate. Figure 3 shows data for the US, but the “Marshall Plan” helped spread economic growth to Europe, as well.

The rising oil prices in 1973 and 1974 brought the growth of oil consumption down to a much lower level. Without low-priced oil, inflation and recession became much more of a problem.

[2] Interest rate changes are being used to offset problems caused by too much or too little oil supply growth.

Figure 4 shows that rising interest rates acted as brakes on the economy up until 1981. Figure 3 shows that this was a period when the purchasing-power of workers was rapidly expanding, indirectly because of the rising supply of cheap oil. The reason why these higher rates slowed the economy is because higher interest rates make it more expensive to finance high-cost purchases. These higher interest rates also tended to hold down price appreciation of assets such as homes and shares of stock because fewer buyers could afford them.

Lowering interest rates over the four decades beginning in 1981 acted in the opposite direction. These lower interest rates made major purchases more affordable, allowing more people to afford a given home or farm. This tended to raise home and farm prices. In the US, refinancing mortgages at lower interest rates and taking out some or all of the price appreciation on the property became popular, further adding to purchasing power. These changes acted to boost the economy, hiding the growing problems with high-cost oil supply.

[3] The world now seems to be hitting two limits at once: (a) Crude oil supply is not keeping up, and (b) Interest rates are stubbornly high.

Figure 5 shows that world crude oil production (relative to population) was lower in June 2024 than for any month since June 2022. The June 2024 production level was much lower than in 2019, before the drop-off in oil production related to Covid-19 restrictions. A longer view strongly suggests that the peak in world oil production took place in 2019.

Based on the high prices experienced in the 1970s, many people today assume that inadequate oil supply will be signaled by high prices. Instead, what is happening now is more of an affordability problem. There are more young people with student loans who cannot afford cars or families. There are many people with college degrees working at jobs that do not require advanced education, and thus do not pay well. There are more immigrants earning low wages. Because of these factors, overall demand tends to stay too low to encourage the development of new, more marginally profitable, oil wells.

Interest rates shown in Figure 4 have risen sharply since 2020. Governments in many countries have raised debt levels, but this added debt has not resulted in a corresponding amount of goods and services being added. The problem is that the oil supply needed to produce these goods and services isn’t rising sufficiently. Instead, the added debt has tended to produce inflation.

Currently, politicians around the world want to add new programs (financed by debt) to help their economies out. If this new debt actually gets more oil out of the ground (through higher oil prices), it may be helpful. But, so far, the additional spending isn’t producing a corresponding amount of goods and services; instead, inflation is tending to stay rather high. This is a sign that limits on inexpensive-to-extract crude oil are being reached. With more inflation, interest rates on mortgages will remain stubbornly high, and economies will deteriorate.

Governments may want to reduce long-term interest rates, but they cannot do so without having the market for these loans disappear. In this part of the economic cycle, it appears that high interest rates, indirectly due to inadequate inexpensive-to-extract crude oil supplies, act as a brake on the economy instead of high oil prices. This confuses those who are expecting high oil prices to signal inadequate supply!

[4] Citizens are not being told about the shortage of low-cost crude oil. Instead, a climate change narrative is being emphasized.

In the 1970s, huge spikes in oil prices led to an immediate understanding that the world had an oil problem. But the fact that the economy has gone on since then, and oil prices are no longer up in the stratosphere, has led people to believe that the shortage problem has gone away. Adding to this belief is the fact that there seem to be substantial oil resources that can be extracted with current technology if the price is high enough.

With a different model, based on the amount of fossil fuels that might be available (if prices could rise high enough, for long enough), it is possible to conclude that if the world continues to extract fossil fuels as it has in the past, this will contribute to rising CO2 levels. This, in turn, could have an impact on the climate.

In my opinion, we are currently facing a serious shortage problem today, not only with crude oil, but also with coal. World coal consumption, relative to population, has turned down in the period since 2012.

The problem with coal seems to be similar to oil; there seems to be plenty of coal in the ground, but prices won’t rise high enough, for long enough, to allow extraction of the higher-cost coal.

Anyone looking at the situation, regardless of their perspective, would say, “We truly need something other than oil and coal to supplement our current energy supply.” The question becomes, “How can this issue be framed to be moderately acceptable to the public?” President Jimmy Carter, back in 1977, talked about the energy crisis and the need to use less oil, but he was not re-elected. Citizens didn’t like the idea of changing their lifestyles.

Somehow, the plan was developed to frame the problem as a climate change problem. This approach had multiple advantages:

(a) This approach would perhaps lead to finding some alternatives to oil and coal.

(b) Citizens would be able to feel virtuous, as they voluntarily endured higher prices and lower energy supplies, during the hoped-for transition.

(c) This approach would allow huge investment opportunities for businesses, including oil and gas companies. Higher profits would perhaps follow. Universities would also benefit.

(d) The economy would show higher GDP because of the growing debt used to finance the so-called renewables. Job opportunities would develop.

(e) Framing the conversation in terms of a climate change narrative instead of the crude oil shortage narrative conveniently leaves out the importance of very low energy prices for the affordability of finished goods. This narrative also leaves out the importance of an adequate total quantity of energy products to maintain GDP growth. Economists didn’t understand either of these issues.

(f) When the carbon emissions goals were announced in the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, the goals had the indirect effect of shifting industry from the US and Europe to China and other Asian countries. Because of the use of very inexpensive coal and low-cost labor, the shift would allow for the world production of manufactured goods to grow at very low cost. Businesses in the US and Europe could hopefully take advantage of this shift because US and European oil and coal supplies were becoming depleted, making it impossible to make this change without the assistance of coal supplies from China and elsewhere.

[5] The world economy is already facing a not-enough-to-go-around problem that plays out in many ways. These not-enough-to-go-around issues contribute to conflict.

(a) Exporters are not getting high enough prices for their exported oil. Revenue from oil is used both to support the development of new fields and to provide tax revenue for governments to provide services for their citizens. If oil prices were $100 to $150 per barrel, exporters would have the additional revenue needed to support their economies. This is a major reason why Russia and Middle Eastern countries are in turmoil.

We don’t think of low oil prices as a not-enough-to-go-around issue, but it is. Shortages of fossil fuels of any kind tend to slow the growth in the supply of finished goods and services that use those products. The part of the world economy left behind can be the producers of fossil fuels, even more than the consumers.

(b) Natural gas export prices have tended to be too low. Low pipeline natural gas prices to Europe were a major reason why Russia wanted to shift its natural gas exports toward China and other Asian countries, where prices might be higher. US natural gas producers are also unhappy about the low prices they get. The US would be happy to push Russia out as a natural gas exporter to Europe.

(c) The Advanced Economies have reduced industrialization because of depleting oil and coal supplies. They have substituted the sale of services.

The US first shifted away from industrialization in 1974, immediately after it discovered that its non-shale oil supply was declining, and the price of additional oil would need to be much higher. A further shift occurred after the 1997 Kyoto Protocol.

At the same time, the industrial production of the “Other than Advanced Economies” (including China, Russia, and Iran) has soared. The industrial production of these economies now exceeds that of the Advanced Economies (including the US, most of Europe, Japan, Australia among others–defined as OECD members).

What oil is available is increasingly consumed by the “Other than Advanced Economies.”

(d) Consumption of the main products of crude oil is being squeezed down by strange temporary economic downturns, especially in the Advanced Economies.

Advanced Economies seem to be adversely affected far more than less advanced economies, partly because industrialization is essential; services can more easily be eliminated.

(e) Poor people of the world are especially affected by the not-enough-to-go-around phenomenon, while wealthy individuals and corporations amass more wealth and power.

This is a physics issue that plays out in many ways. Young people, in particular, find it difficult to make adequate wages to afford a home and family. Even young people who obtain higher education find it difficult to succeed.

Major foundations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, gain power over what would appear to be independent organizations, such as the World Health Organization, by making huge donations. Regulators of many kinds become tied to the groups they regulate, making decisions that favor the companies that they are supposed to be regulating over the welfare of the individual citizens that they are supposed to be protecting.

In the current situation, the general public feels increasingly powerless, and many feel the urge to take matters into their own hands. All these things add to the conflict situation.

[6] The United States has been the leading world power, but its ability to defend other countries militarily is rapidly eroding.

While Ukraine, Israel, Taiwan, and members of the EU would like to think that the US can adequately defend their interests militarily, this ability is rapidly eroding. Today, nearly every type of manufacturing in the US requires supply lines from around the world. It is difficult to supply needed military aid to countries overseas, without placing an order for supplies from a country that the US is increasingly in conflict with.

Even the supply of electrical transformers to replace damaged ones in war zones raises a question of whether a sufficient supply can be assured to meet the demand for replacements for storm-damaged transformers in the US. Long lead times are often required to obtain transformers in the US, even in the absence of any additional demand for them.

The US tends to use sanctions to try to get other countries to do as it prefers. This approach doesn’t work well because sanctioned countries learn to work around the sanctions. Increasingly, in the BRICS countries, steps are being taken to move away from the US dollar as the standard for trade.

As long as the US is the accepted world leader, other countries that are involved in conflicts (which are indirectly about energy supply) will try to draw the US in to support them. Ukraine has been having energy problems for a very long time.

The EU, the UK, and Israel all seem to want war, and they would like the US to help them.

In 2023, US per-capita oil consumption is more than double that of the EU, UK, and Israel at the same date. The US’s total energy consumption per-capita is more than four times that of Ukraine. These countries assume that the US can provide the weapons and other assistance they need. But the countries they are fighting against know that the US is dependent upon supply lines that extend around the world. Actually, the US’s ability to provide help is quite limited. This adds other areas of conflict.

[7] The shift to wind and solar electricity is not working out as planned.

While the US has added wind and solar capacity, it has not added to the per-capita electricity supply. It is too expensive when all the costs are considered, and it is often not available when needed.

Communities are figuring out that if they really want a larger electricity supply (to support electric vehicle use or growing artificial intelligence demands), they need to add something other than wind and solar. In the US, this usually means added natural gas electricity generation. There are also at least two plans to reactivate closed nuclear plants in the US.

The EU has not had any better success at ramping up per-capita electricity generation using wind and solar (Figure 14).

A glance at Figure 7 (above) suggests that industrialization doesn’t really come from an expanded electricity supply. Inexpensive fossil fuels seem to be the base of industrialization, and the world is increasingly short of these.

While approaches for moving away from fossil fuels, other than wind and solar, are being tried, success at an adequate scale seems to be far away.

[8] It is hard to tell the rest of the story in detail.

We live in a finite world. All parts of the economy operate in cycles. In fact, individual people, individual businesses, and individual governments all have finite lifespans. We now seem to be coming to the end of an economic cycle. We don’t know precisely how this will end. We do know, based on history, that the downward part of the cycle will likely take years to resolve.

We as individuals are hard-wired to prefer “happily ever after” endings to our narratives. This is why people who believe that we are running short of fossil fuels tend to believe that if we just try a little harder, we can extract more oil, natural gas, and coal. There must be enough resources in the ground if we focus our efforts in that direction.

On the other hand, people who believe that climate change is our biggest problem seem to think that we can transition to using a modest amount of renewable energy instead. Unfortunately, the physics of the situation doesn’t allow things to play out that way. Also, our so-called renewables are built on a base of oil and coal. If we can’t get enough oil and coal out, already built renewables will stop functioning within a few years, and new ones will be impossible to build.

Nearly everyone who does modeling assumes that the future will be very similar to the past. Analysts assume that the economy can continue to grow forever. They assume that it is possible to pull larger and larger amounts of resources from the ground. It is easy to assume that leaders will look out for the best interests of all their constituents, and that businesses will act ethically. But we have already begun to see evidence that these assumptions don’t necessarily hold. The fact that some people can see that changes are coming, while others cannot, is part of the reason for the current conflict.

A major problem that the world faces is the fact that while governments can print more money, they can’t print more resources. Thus, broken supply lines are likely to become more common. Wars may need to be fought in new ways–for example, taking down other another country’s internet or electrical grid. Pensions will likely need to be cut back greatly, or they may ultimately disappear completely.

We don’t know how this all will end, but a great deal of conflict of one kind or another seems very likely in the next few years.